Chapter 59: Git Branching Models

Slide Deck Git Practices Slides

Git Branches

A branch in a git repository is just a name associated with a particular commit.

- This page from the Git book describes how branches work.

- This page from the Git book describes how branches can be used.

- This page from the Git book discusses the fundamentals of some branching workflows.

In general, I would recommend giving all of Chaper 3 a read.

Things to discuss:

- “Topic” or short-lived branches

- “Silo” or long-running branches

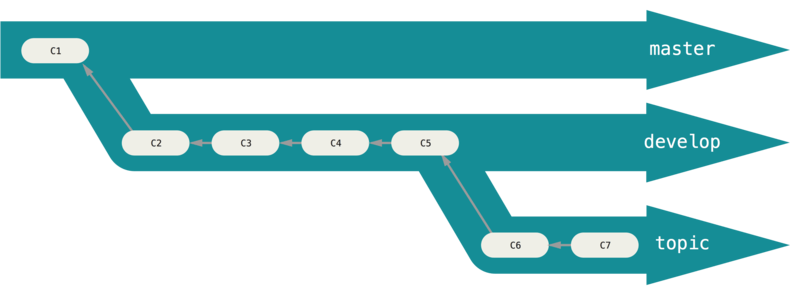

Gitflow

Gitflow is a strict set of rules for handling branches in a git repository.

There are two main branches that live forever:

master: each commit on this branch is a production-ready release of your softwaredevelop: current work is merged into this branch from other branches. Once it reaches a stable state, a release is merged ontomasterfrom here

In additional to the two main branches, there are a large number of supporting branches. These branches are short-lived and are deleted after they are merged. They come in three varieties:

- Feature branches

- Release branches

- Hotfix branches

Feature Branches

Feature branches are used to develop new features.

They branch off from develop and are merged back into develop.

The are named whatever you want, and should typically not be synchronized with the origin repository.

Release Branches

Release branches are used to prepare the repository for a release.

This can include making sure all test cases pass, updating documentation and version numbers, and minor bug-fixing.

They branch off from develop and are merged back into both develop and master simultaneously.

They are named release-* where the * is the name of the release.

Hotfix Branches

Hotfix branches are used to fix bugs on a released version of your software.

They branch off from master and are merged back into both develop and master.

Summary

This is a very rigid structure for a repository, and it may sometimes not be worth the headache of implementing, but at the very least it serves as a good set of ideas to apply when managing the workflow of your project.

When merging in Gitflow it is recommend to use the --no-ff flag so that a commit is always created to record history of the merge.

This is interesting because it is a move in the complete opposite direction of Git methodologies that encourage rebasing.

Instead of trying to hide the development history of your project, Gitflow encourages recording it in great detail.

Is using Gitflow a good idea? Consider this article:

What are the problems?

- The large number of

--no-ffmerge commits can create a rather messy history when several people work in the same repository. - The

masteranddevelopbranches are largely redundant. Releases are tagged in themasterbranch anyway, so the branch itself doesn’t serve much purpose (besides making the history even messier). - All these branches and rules (I only outlined the main rules in my summary above) only work when everyone succeeds in following the rules. When people make mistakes, the model falls apart. Git history is by definitely something which cannot be fixed if it’s broken.

OneFlow

OneFlow is an alternative git branching model proposed by the author of the “GitFlow is harmful” post above.

It is different from GitFlow in the following ways:

- There is only a single main branch, let’s call it

master. - Rebasing is used to integrate changes into the

masterbranch, so that history is linear. - There are fewer overall rules, and instead the basic principles of Gitflow are maintained:

- We use feature, hotfix, and release branches to organize the work that developers are doing.

- We use tags to indicate which commits in the repository represent releases.

- We integrate changes from branches into the main branch, then delete the unused branches.

GitHub Flow

Most of you will probably be using GitHub to manage your repositories this quarter so it’s worth taking a look at the branching model that GitHub supports and recommends.

In general, the main thing to know about how GitHub works is using Pull Requests, or PRs.

When you create a PR on GitHub, you indicate that you would like to have some set of changes merged into the project.

The most common scenarios is that you want to merge your changes from a fork into the original project,

or you want to merge a branch you created into master.

In this class I’d recommend going with the branch option since forks are mostly useful when developers aren’t working together but are working on the same thing (i.e. the open source community).

The best thing about PRs, in my opinion, is that they:

- Provide a medium for performing code review, since everyone has an opportunity to read the commit log and diff before code is merged into master.

- Encourage a lightweight branching model that is organized in one central place.

- Make it easy to associate work with items in your repository’s issue tracker.

A simple and effective rule to use with PRs is that someone other than the author of the PR must merge it.

Through the GitHub interface you also get to choose whether your changes are integrated with a merge commit, rebase, or squash commit.

Git Tips

How to avoid merge conflicts

- Use consistent style across team

- How many space is a tab? Is a tab spaces at all?!

- Naming rules for everything

autocrlfoption- A must-have when some users use Windows and others do not.

- Frequent commits!

- Communication - have ownership of code and communicate requirements

- Issue trackers and a branching model go a long way